Significance

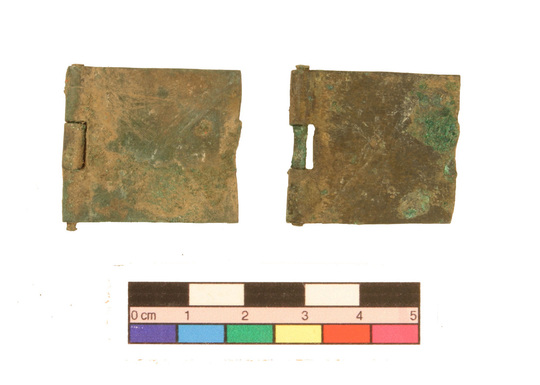

The object is a series of ten copper alloy rectangular belt-plates with hinged ends and a crescent-shaped pendant linked to one plate with a flat copper alloy loop. The plates are attached to one other via a hinge mechanism. The mechanism consists of two loops folded over at one end of each plate that hold a pin; the next consecutive plate is attached to the same pin via one loop folded from one end of the plate.

On all of the larger plates (not the final short one) there is evidence for incised decoration on one surface in the form of lines scratched diagonally from corner to corner creating a rough X (below).

A small section of twisted fibres, resembling string, was found wedged into the hinge of the final shorter plate.

The object was found by a metal detectorist called Sam Smith on his father’s land in West Stow, Suffolk, in February 2010. The object formed part of a Roman hoard of copper alloy objects, probably in a ceramic container standing vertically in the ground. The field in which the hoard was found was previously known as a Roman site, from which many Roman objects have been removed by metal detectorists, including 336 coins ranging in date from 1st-2nd century BC to AD 388-402. The object was initially thought to be a belt, but it does not appear to be long enough, assuming that all the pieces are present, which is not certain, and there is no way of fastening it, the pendant being decorative and not functional as a buckle. It may have been a piece of decorative military attire for people or horses that dangled with the pendant at the lower end, possibly from a belt or bridle.

On all of the larger plates (not the final short one) there is evidence for incised decoration on one surface in the form of lines scratched diagonally from corner to corner creating a rough X (below).

A small section of twisted fibres, resembling string, was found wedged into the hinge of the final shorter plate.

The object was found by a metal detectorist called Sam Smith on his father’s land in West Stow, Suffolk, in February 2010. The object formed part of a Roman hoard of copper alloy objects, probably in a ceramic container standing vertically in the ground. The field in which the hoard was found was previously known as a Roman site, from which many Roman objects have been removed by metal detectorists, including 336 coins ranging in date from 1st-2nd century BC to AD 388-402. The object was initially thought to be a belt, but it does not appear to be long enough, assuming that all the pieces are present, which is not certain, and there is no way of fastening it, the pendant being decorative and not functional as a buckle. It may have been a piece of decorative military attire for people or horses that dangled with the pendant at the lower end, possibly from a belt or bridle.

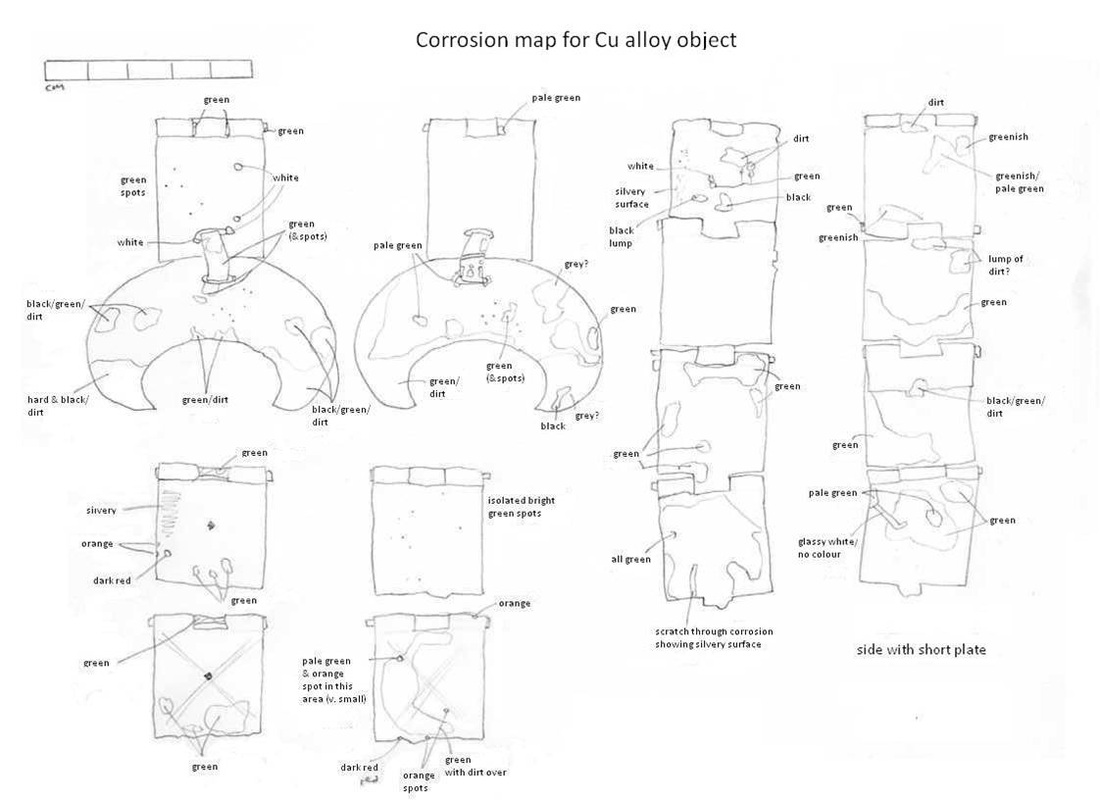

Pre-treatment condition

Seven of the belt-plates were still hinged together when the object was received for treatment at UCL; the plate at one end of the hinged section is very short, but appears to have been designed this way rather than broken off, as it has the beginnings of the next loop at the loose end. There were green corrosion products present on all pieces, which were thought to be malachite; some tiny areas of red, most likely cuprite, were also visible, and examination under a microscope suggested they may have formed warts into the underlying cuprite that forms at the level of the original metal surface. Much of the green corrosion product was covered in a thin layer of dirt/soil, and there were also a few larger lumps of soil on the plates, and soil particles, including tiny pebbles, in the crevices formed by the hinges. In many areas there were also some black/grey corrosion products, probably tin oxide.

There were some areas of nantokite visible, where the corrosion products appeared soft and pale grey. The couple of small areas of pale green corrosion were thought to be unlikely to indicate the presence of paratacamite, because they were not large or powdery.

There were some areas of nantokite visible, where the corrosion products appeared soft and pale grey. The couple of small areas of pale green corrosion were thought to be unlikely to indicate the presence of paratacamite, because they were not large or powdery.

Treatment

The treatment decided upon was to clean off soil and dirt, re-shape the object so all surfaces were visible, and remove only the corrosion that was thought to be obscuring details. The object was also assessed for signs of corrosion that may continue to damage it in the future.

The re-shaping was done in order to make all surfaces visible to check for active corrosion, and accessible to clean. It also made the object more understandable and easier to display.

The reasons for not cleaning all the corrosion were:

As treatment progressed, it became clear that the two separated plates and the plate hinged to the pendant could be re-joined to each other.

Cleaning of dirt was undertaken on all surfaces. This was done mechanically with a cotton wool swab and industrial methylated spirits (IMS).

The removal of corrosion products was mostly done using a blunt scalpel, but cotton wool swabs with IMS were also used to remove residue and some nantokite, which is soft.

Reconstruction / repair

The chain of 7 plates were straightened into a long, flat chain by very slowly unbending opening the bend. This was done by hand over the course of about 2 hours, with some IMS applied to soften any corrosion products that may be hampering the process.

The hinges to be re-joined were initially fixed with Araldite 2020 (an epoxy resin). Over the hinge joins was laid small sections of long fibre hand-made tissue coloured with watercolours and impregnated with 20% weight/volume Paraloid B44 (a methyl methacrylate co-polymer) in acetone. These were laid in place, and the adhesive was reactivated by applying a drop of acetone to the tissue. Then a final drop of adhesive was applied. Experimentation on a practice object had found this to be the best method of blending the tissue in to the colour of the object. The joins made were initially examined carefully under magnification, and the fit of each join was very good. However, this meant that one of the plates was the “wrong” way round. This must have been a “mistake” that occurred during manufacture, because the join was very close and clearly the plate would have originally been fitted on in this way.

Packaging

The packaging had to take into account the unknown future of the object. It was decided to use a polypropylene container, which will maintain a fairly stable microclimate if it is left unopened, helping to buffer the inside environment around the object from changes in relative humidity. Ideally the object should be kept below 46%. To assist in this aim, the bottom of the box was filled with silica gel, a desiccant.

The re-shaping was done in order to make all surfaces visible to check for active corrosion, and accessible to clean. It also made the object more understandable and easier to display.

The reasons for not cleaning all the corrosion were:

- leaving some corrosion products present left the object with the evidence of some of its history, given that it was buried for so long, and also a visual reminder of the context in which it was found

- some of the malachite was very aesthetically attractive

- time limits meant that it was impractical to clean off all of the corrosion products

As treatment progressed, it became clear that the two separated plates and the plate hinged to the pendant could be re-joined to each other.

Cleaning of dirt was undertaken on all surfaces. This was done mechanically with a cotton wool swab and industrial methylated spirits (IMS).

The removal of corrosion products was mostly done using a blunt scalpel, but cotton wool swabs with IMS were also used to remove residue and some nantokite, which is soft.

Reconstruction / repair

The chain of 7 plates were straightened into a long, flat chain by very slowly unbending opening the bend. This was done by hand over the course of about 2 hours, with some IMS applied to soften any corrosion products that may be hampering the process.

The hinges to be re-joined were initially fixed with Araldite 2020 (an epoxy resin). Over the hinge joins was laid small sections of long fibre hand-made tissue coloured with watercolours and impregnated with 20% weight/volume Paraloid B44 (a methyl methacrylate co-polymer) in acetone. These were laid in place, and the adhesive was reactivated by applying a drop of acetone to the tissue. Then a final drop of adhesive was applied. Experimentation on a practice object had found this to be the best method of blending the tissue in to the colour of the object. The joins made were initially examined carefully under magnification, and the fit of each join was very good. However, this meant that one of the plates was the “wrong” way round. This must have been a “mistake” that occurred during manufacture, because the join was very close and clearly the plate would have originally been fitted on in this way.

Packaging

The packaging had to take into account the unknown future of the object. It was decided to use a polypropylene container, which will maintain a fairly stable microclimate if it is left unopened, helping to buffer the inside environment around the object from changes in relative humidity. Ideally the object should be kept below 46%. To assist in this aim, the bottom of the box was filled with silica gel, a desiccant.

Condition after treatment

The object is stable in terms of corrosion, and the packaging should assist this situation for a while longer.

The object has been improved aesthetically by the removal of the soil and some of the corrosion products, while still keeping some corrosion to keep the object looking as found, which preserves some of its history; looking new and shiny would be misleading. It is also more understandable, because the long section has been unbent and the separate pieces joined as far as possible.

The joins are very fragile due to the small surface area of the join, although if the epoxy fails, the tissue will hold the joins in place. Hopefully the packaging displays the object in such a way that removal from the box will not be considered necessary very often.

The object has been improved aesthetically by the removal of the soil and some of the corrosion products, while still keeping some corrosion to keep the object looking as found, which preserves some of its history; looking new and shiny would be misleading. It is also more understandable, because the long section has been unbent and the separate pieces joined as far as possible.

The joins are very fragile due to the small surface area of the join, although if the epoxy fails, the tissue will hold the joins in place. Hopefully the packaging displays the object in such a way that removal from the box will not be considered necessary very often.

Recommendations for future care

Ideally, the object would be kept at below 46% RH; it should not be kept in a damp environment. The silica gel should be changed once a year, or when it changes colour (from yellow to green).

Handling should be kept to a minimum, because the joins are very fragile. When handling, wear gloves because sweat and oils from hands can cause the metal surface to tarnish and corrode.

Handling should be kept to a minimum, because the joins are very fragile. When handling, wear gloves because sweat and oils from hands can cause the metal surface to tarnish and corrode.